Screenshot from Plan International UK report

Our girls are scared. Frightened when they are outside, on public transport or on the street. Uncomfortable when they are online. Uneasy in leisure facilities. Hyperbole? I wish it was, but in a significant study published earlier this week, 93 per cent of girls and young women from across the UK said they do not feel ‘completely safe” in public spaces. Despite being permanently attached to their smartphones and tablets, only one in ten say they feel safe when they are online, and the majority (89 per cent) insist they are ill at ease in public swimming pools and other leisure spaces.

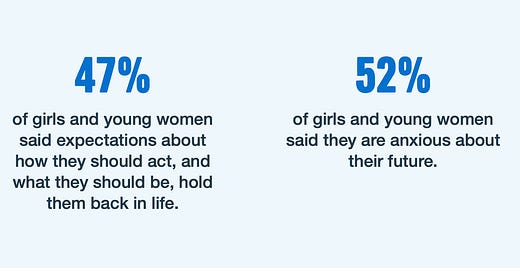

The State of Girls Rights in the UK report, published by children’s charity Plan International UK, paints a depressing picture of a generation of girls born in the 21st century but still hidebound by Victorian attitudes towards their sex and their lives defined by class. The survey, which explored factors affecting the girls’ lives such as education, poverty and violence, ranked Clackmannanshire as one of the ten toughest places in Britain for girls. Yet only 36 miles from Alloa, in the leafy streets of Milngavie, live girls fortunate enough to be born in the best place in the country. According to the report, East Dunbartonshire is the number one council area for girls to flourish, with East Renfrewshire coming in at number nine. Glasgow is in the bottom 20 per cent, with nearly a third of children living in poverty and 42 per cent leaving school without good grades. Even Edinburgh, long considered to be a wealthy city, is failing its children. The survey reports that 37 per cent of the capital’s young people leave school with nothing much to show for their studies, and 20 per cent of children live in poverty. As the report says, where you live and who you are still matters in 2024, far more than it should. And for girls, their sex matters. Just as it always has done.

Gender stereotypes persist

Sixty years after their grandmothers’ generation burned their bras in a symbolic act of freedom, more than half of young women aged between 17 and 21 years old say that the way they look “holds them back”. And despite being told by society they can be anything they want to be, as they mature they find that the reality is somewhat different. Gender stereotypes persist. Women are expected to behave differently from men, to be kind and to look pretty. And this before the girls hit the harsh reality of the workplace. Despite progress such as parental leave and equal pay legislation, the world of work is still largely designed by men for men. HR departments may argue that they take into account the difference between the sexes, particularly a woman’s reproductive role, but real life suggests otherwise. Childcare costs are prohibitive. Working patterns are not conducive to family life. Little wonder that fertility rates across the UK are at their lowest since records began as young women struggle to combine motherhood with work.

As they stand on the cusp of adulthood, what do the girls who took part in Plan International’s survey think should be done to improve their lives and those of their sisters? More than half say that changing the attitudes of boys and men towards women would help them feel safer. But in a society where violent pornography is freely available on every schoolboy’s smartphone, and almost half of 16-21 year-olds expect sex to involve physical aggression, what hope does a parent or teacher have in persuading boys – and girls – that sexual violence is not the norm?

The girls are disdainful of the role of politicians in changing attitudes and behaviour, sceptical that they can build a fairer, more equitable society. Three in five do not trust politicians at all, and as they grow older this increases to 70 per cent of young women with no faith in the political process. Yet how else are we to build a better society for our girls if not through representative democracy?

No more gimmicks

Perhaps our politicians could start by making fewer grandiose but essentially empty promises. Nicola Sturgeon’s promise to close the poverty-related attainment gap that divides Scotland by 2026 was nothing more than cynical rhetoric, as the Plan International survey shows. It is not just nationalist politicians either who indulge in careless talk. The Conservatives’ flagship Levelling Up policy, which was to transform Britain, proved to be a damp squib with only 10 per cent of promised funds actually spent by March this year. And the new Labour government has already been lured into the trap of making eye-catching but fatuous commitments. Anneliese Dodds, the women’s and equalities minister, promised on social media earlier this week that there will no “no more gimmicks”, yet in the same post she boasted that Labour will bring forward plans to “halve violence against women and girls”. She offered no evidence on how the new government would achieve this miracle, just a throwaway line that no doubt will come back to haunt her in the years to come. Far better if she had said she was determined to reduce violence, but knew it was going to be tough and would require everyone, from parents to the police, politicians to community leaders, to play their part.

There are no quick solutions to the problems that blight so many young women’s lives. We have, all of us, helped create a society where girls feel unsafe, where their life chances are still determined by class and sex, not ability or talent. We have allowed politicians to dazzle us with strategies and selfies and the result is a generation of girls who are afraid to walk the streets and are fearful for their future. We should all hang our heads in shame.

This article was first published in the Scotsman on 21 July 2024